Complete Streets Implementation in Sacramento

Sacramento, California

Source: Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center (PBIC)

Problem

Streets should be designed to accommodate all users, promote sustainable transportation, and make neighborhoods and the urban core more livable. However, where a city has quickly expanded into a previously rural area, country roads may be widened to accommodate more motor vehicles without considering the needs of other users. This happened in Sacramento, California. Challenged to improve deficient streets, the city adopted complete streets policies, plans and standards to meet its goals.

Background

In Sacramento, large annexations and years of double-digit population growth drove the expansion of low-density, automobile-oriented residential and commercial development. Many wide arterial streets were built and older, rural roads were widened to accommodate more vehicles, without much consideration for the needs of other road users, particularly pedestrians. By the late 1990s, the city faced a legacy of missing sidewalks, curbs, gutters, bike lanes, street lights and street trees; residents complained of high traffic speeds and missing pedestrian amenities. Traffic calming measures helped reduce speeds on existing streets but were expensive and did not address design issues for new streets. Growing concerns about air quality and pedestrian safety, as well as pressure from developers, who argued that earlier standards were too rigid, and residents, who demanded more livable neighborhoods and better pedestrian amenities, fostered the necessary political environment to support new street design standards.

Solution

In 2004 the city of Sacramento adopted revisions to its street standards. The process included public involvement and outreach to specific stakeholder groups, including emergency responders, the disabled community and developers. These Pedestrian Friendly Street Standards were intended to enhance the pedestrian environment, promote alternate transportation modes, and improve safety for pedestrians and cyclists.

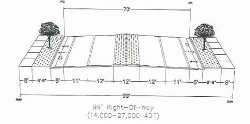

The resolution adopting the new standards states in part that, "The city street system should encourage alternate mode use, especially walking and bicycling, by working toward a balance of all street users." It lists eight objectives for city streets and shows cross sections of streets that include planting strips between the sidewalk and curb for the purpose of growing shade trees, vertical curbs instead of the longtime standard of rolled curbs, reduced parallel parking lane widths and increased bicycle lane widths. These cross sections are used for all new streets and wherever possible in retrofit situations.

Image Source: Edward J. Cox

When the Pedestrian Friendly Street Standards were adopted in 2004, Sacramento did not have an explicit Complete Streets policy. However, the existing general plan was amended to include the new standards and the city's Pedestrian Master Plan (2006) references them. The 2030 General Plan, passed in 2009, specifically refers to complete streets as a citywide mobility goal and recommends implementation policies (Section M 4, Goal M 4.2).

Results

Since the new standards were adopted, Sacramento has used the following methods to complete its streets:

New streets

Most new streets are coincident with new development, and will be completed first. Because cities can impose new standards, new streets can include all provisions for all users at one time. It is useful to look at recently constructed streets to see how the current standards can be updated, a process the City of Sacramento used to make the "Pedestrian Friendly Street Standards."

Adding sidewalks

The most significant element of a complete street is a walkway for pedestrians. Sometimes a sidewalk can be added where the curbs, gutters and even trees already exist. If the public right of way has sufficient room, an infill sidewalk might be installed. The cost to add only sidewalk is relatively inexpensive; Sacramento has realized greater savings by using city road maintenance crews to do the work. When sidewalks are added to streets without curbs and gutters, more detailed attention is required for proper drainage.

Image Source: Edward J. Cox

Adding bicycle lanes

The addition of bicycle lanes has multiple benefits for street users. Bicycle lanes create a greater separation between automobiles and pedestrians; the perceived narrowing of the travel lanes can help slow motor vehicles. When used for maneuvering space for parallel parking, bike lanes help to reduce conflicts.

The best opportunity to add bicycle lanes is when the street is being re-surfaced. This process offers a blank slate with which to work. It may be possible to add bicycle lanes by shifting the centerline of the road, putting parallel parking on only one side of the road, or some other rearrangement of the roadway. Other streets may have too much pavement space, and a solution might involve striping a second/adjacent bike lane where the pavement is better quality, or to paint out excess paved areas.

An important precursor is a bikeway plan that identifies streets that should be considered for bicycle lanes. This plan is referred to when specific street segments are to be resurfaced.

Dropping travel lanes

Sometimes called a road diet, the more specific term "lane drop" is used where a road's capacity is greater than the space needed for the motor vehicle traffic using it. The excess roadway space is then redistributed to provide for bicycle lanes and other functions. A traffic analysis should be prepared to verify that there are no significant issues with removing a travel lane.

One of the simplest lane drop projects occurs when there are two travel lanes in one direction and one lane in the other direction. Typically daily traffic demands on a road are equal for both directions, so it may be possible to drop the extra lane.

Another kind of lane drop can be done on three-lane, one-way streets. Once it was determined that there would not be any significant impact on traffic, Sacramento converted some of its one-way streets from three lanes to two lanes. The resulting space was divided into left and right side bicycle lanes. This lane drop has made pedestrian crossings shorter and left turning easier for cyclists.

Image Source: Edward J. Cox

Elsewhere, conversions from two lanes in each direction to one lane each way with a center two-way left turn lane has resulted in better traffic operations, since left turning vehicles are no longer in the path of forward moving vehicles.

Two-way conversions

During the 1950s, Sacramento converted several two-way streets into one-way operation as a means of solving congestion problems. After 50 years of three-lane one-way operation on some of its central city streets and the addition of new freeways, there has been a movement to convert streets back to two-way operation. This has produced more pedestrian and bicycle friendly streets. Making two-way conversions requires a large amount of preparation, including public outreach and traffic studies. Two-way conversions can be costly as well, since additional signal equipment is needed at intersections and at railroad crossings.

Shortening crossings

Shortening the crossing distance can assist pedestrians in crossing a street. Excess pavement can be blocked out. Even better, corner bulb-outs can be installed to cut down on the crossing distance. Wider bicycle lanes on the approach side of a signalized intersection can be used in lieu of right turn slip lanes. This alternative to the "pork chop" island allows for one straight crossing as opposed to multiple interactions between pedestrians and motor vehicles.

Widening the sidewalk

In areas where a large amount of pedestrian traffic is expected, it is appropriate to widen the sidewalks. These projects usually involve modifying old infrastructure, which in some cases is historic. Special attention with respect to details such as curbs and railings is required, so as to not introduce any inconsistent elements into historic fabric.

Adding parking

Adding automobile parking has been an effective method to create visual friction to slow down motorists and to provide a buffer for the pedestrian. While parallel parking is a frequently used application, angled parking also has been used successfully. Of great interest to bicyclists is the use of back-in angled parking. By having cars back into the angled stall, there is better visibility between bicyclists and motorists as they leave the parking space.

Parking isn't just for automobiles: bicycle parking is now a recognized city function. Sacramento has converted former parking meter posts into bicycle parking devices. Other bicycle parking programs are forthcoming and may include city-sponsored bicycle parking racks.

Engaging the street

Most discussions of complete streets involve adding elements in the public right of way. On urban streets, however, completing the streets goes beyond the sidewalk to include buildings that engage the street. In particular, buildings with residential above ground-floor retail will keep eyes on the street. The result is a safer and more inviting environment for pedestrians. Outdoor dining areas are often desirable; however, they should be done with sensitivity to maintaining clear access for the people with disabilities.

Conclusion

As existing cities begin to embrace bicycle and pedestrian friendliness within the public right of way, new developments will follow suit. Place-making principles of the city grid with short blocks and through streets are now being introduced in new developments to encourage citizens to be less dependent on automobiles.

The path to complete streets involves balancing competing interests such as the need to make wide sidewalks for large groups of pedestrians versus the need to maximize developable land, or the need to keep crossing distances short versus making intersections that accommodate trucks. There is no single cure for all conditions. Sacramento continues to make incremental improvements to maintain momentum and eventually complete all the city's streets.

References and additional information

Pedestrian Friendly Street Standards Ordinance:

http://cityofsacramento.org/dsd/reference/resolutions-and-ordinances/documents/Resolution-2004-118-Pedestrian-Friendly-Street-Standards.pdf

Sacramento Pedestrian Master Plan (2006): http://www.cityofsacramento.org/transportation/dot_media/street_media/sac-ped-plan_9-06.pdf

Sacramento 2030 Master Plan (Mobility section):

http://www.sacgp.org/documents/04_Part2.04_Mobility.pdf

Success Stories: Sacramento's Pedestrian Friendly Street Standards. Posted on Healthy Transportation, September 11, 2006. http://www.healthytransportation.net/view_resource.php?res_id=4&cat_type=improve

Moving forward: Completed "complete streets" projects as of May 2010 http://www.cityofsacramento.org/transportation/dot_media/engineer_media/pdf/ProjectHandout_11x17_2010.pdf

Sacramento Transportation and Air Quality Collaborative. Best Practices for Complete Streets. 2005. http://www.cityofsacramento.org/transportation/dot_media/engineer_media/pdf/bp-CompleteStreets.pdf

"Planning for Growth Through Complete Streets: Sacramento, California". In Complete Streets: Best Policy and Implementation Practices. APA Planning Advisory Service Report Number 559.

Contact

Edward J. Cox

Bike and Pedestrian Coordinator

City of Sacramento

915 I St., Room 2000

Sacramento, CA 95814

(916) 808-8434

ecox@cityofsacramento.org